It’s been said many times, but it bears repeating: the animal training fields are unregulated. What this means is that there are no requirements in order to declare yourself a dog (or bird, horse, etc.) trainer or behavior consultant, start a business, and charge people money for your services. And while the term “behaviorist” is typically reserved for professionals who have a higher-level degree in one of the animal behavior fields, it’s colloquially not used that way which adds further confusion.

As a result, this profession is a lot like the Wild West. There’s a wide variety of methodologies, ideologies, and levels and types of expertise, but little to no professional accountability. This can make it scary and overwhelming to find good help if you need it. So many behavior professionals out there! And most of them sound very impressive and persuasive! But how do you know? Who can you trust? Who is telling the truth, and who isn’t? Who is effective and who isn’t? This is particularly daunting if you’ve already been burned, and wasted time and money on services that weren’t helpful to you. It takes a lot of bravery and determination to venture back into the Wild West when you’ve already been burned by it.

Despite these uncertainties, there are tools available that can increase the likelihood of finding a professional who can help you and your pet(s) in an efficient and compassionate way. And, in my humble opinion, the best tool in that particular toolbox is one that might sound as daunting and overwhelming as finding the right behavior professional for you! Hopefully, though, you won’t feel that way by the time you’re done reading this article.

The tool I’m referring to is a crucial component of critical thinking skills called epistemology, but you really don’t need to remember that word if it’s off-putting to you. Another way to think of epistemology is “the theory of knowledge”. In other words: what do we actually know? And how do we know that what we know is true? How can we identify reliable, accurate information and distinguish it from misinformation and misleading half-truths?

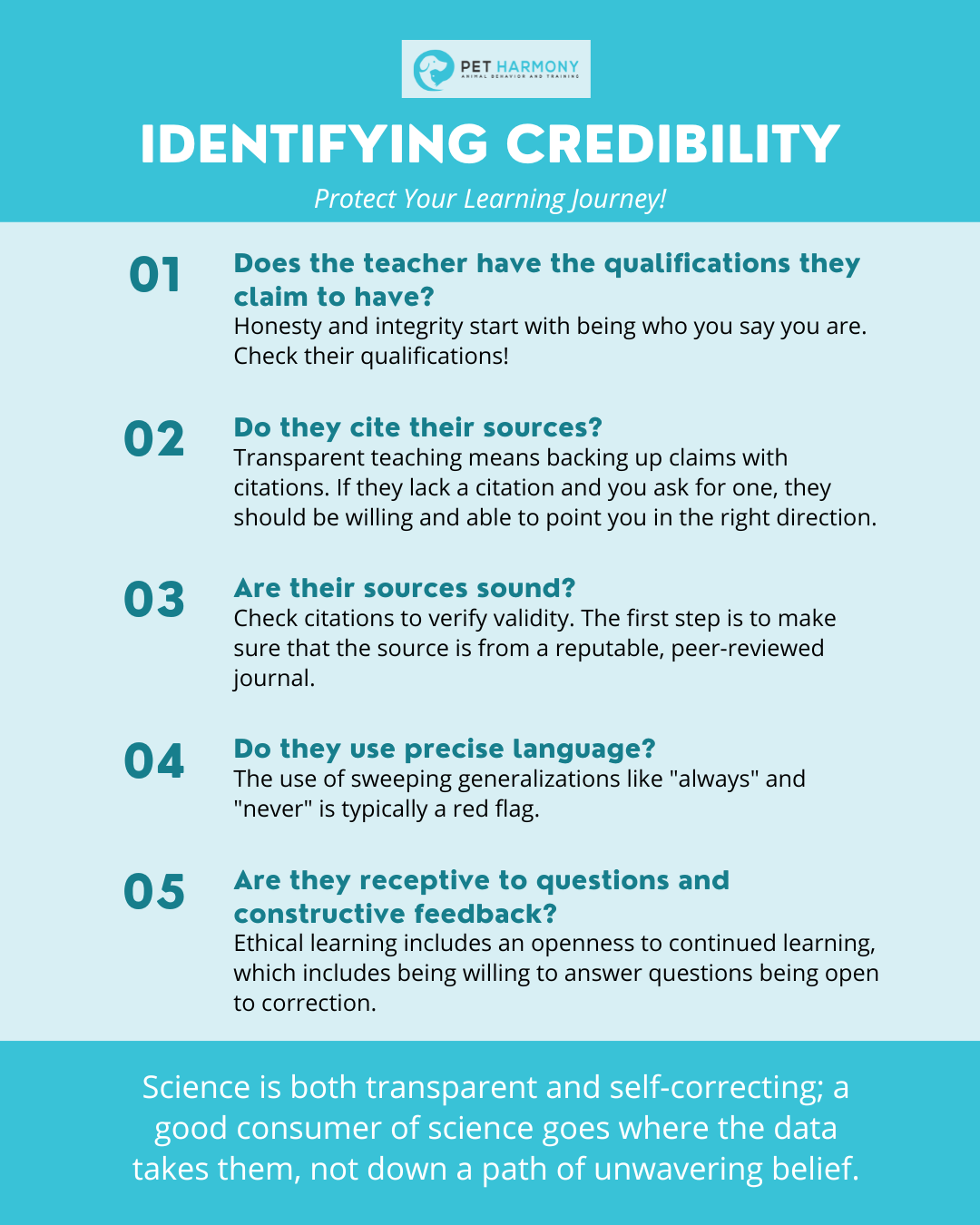

By taking an epistemological approach to selecting an animal behavior professional, you don’t need to become a behavior expert yourself! You just need to learn how to ask yourself these five questions while looking for the right behavior professional for you:

Let’s break each of these questions down and talk about how they apply to finding the right behavior professional for you:

#1. Does the teacher have the qualifications they claim to have?

Because this is an unregulated profession that lacks a clear process for how and what to learn, what competencies to develop and demonstrate, and what kind of assessment process qualifies you to work as a professional within it, individuals and organizations within the field have come up with a seemingly endless list of letters that a person can put at the end of their name. It can make your head spin! Even people within the field struggle to keep track of them all.

But these letters don’t carry equal weight and validity, nor do the titles that go along with them.

Let’s take a look at the various types of titles that you might run across:

College degrees

There are a number of academic fields that can, at least in part, prepare someone for work as an animal trainer or behavior consultant. However, these degrees and their associated titles can be abused or misused in this profession.

For example, just because a person has a PhD at the end of their name doesn’t mean that their degree has anything to do with animal behavior, and therefore does not make them more or less qualified to work in this field. A person with a PhD in botany, for example, may be quite knowledgeable about botany. They may even be quite knowledgeable about animal behavior! But their PhD does not indicate competency in animal behavior.

The other side of that coin is where people give themselves misleading titles that indicate a formal education they do not possess. It is not uncommon to see on a dog trainer’s website that they claim to be a behaviorist, or an ethologist, or a psychologist, or any number of other, similar titles when in fact they have no formal education in any related field.

Action item: check their website to see what, specifically, their degree(s) are in.

Professional certifications

There are a few professional certifications available to animal trainers. These are created by certifying bodies (organizations) which have created a clear rubric for what competency looks like for each certification they offer. People have to go through some kind of assessment process (usually an exam, with or without submitting videos of their training, submitting a client log, submitting case studies and scenarios, or other demonstrations of competency) which is submitted and graded anonymously to prevent the examiner’s bias for or against the individual from influencing their assessment.

It is rare, but every once in a while you may encounter a trainer who claims to have a certification they don’t actually have, or will make up a certification altogether. For example, we once encountered a trainer who claimed to be a certified behavior consultant through Pet Harmony, even though this person had never been through any of our courses or programs–and even if they had, we don’t offer certifications of any kind!

Action item: Do a web search to find the organization that offers the certification. Because several professions may use the same letters, you will probably have to be somewhat specific in your search (e.g. “CDBC dog certification”). Then look at their directory to confirm that the professional you’re looking at is, indeed, listed.

Technical certifications

By far and away, these are the most abundant types of certifications available in this profession. Unlike professional certifications, any behavior professional can create a course or a program of some kind and then create a certification for it. They typically operate alone, therefore lack the professional consensus of a certifying body. These certifications are usually given upon completion of the course without requiring any kind of proof of competency. And even if there is some kind of exam, it typically lacks the anonymity of a professional certification assessment.

To be clear, I’m not saying that these certifications lack any value or merit whatsoever! But all they really indicate is that someone completed a course of some kind and therefore may have a higher degree of proficiency at the specific techniques taught in that course than someone who hasn’t completed it. These certifications really don’t indicate overall competency, efficacy, or ethical comportment.

Furthermore, these certifications are the easiest to abuse. It’s much harder to tell whether someone has actually completed the course associated with the certification. A trainer who has a whole string of these letters at the end of their name may be enthusiastic about learning lots of different techniques, or they may be using those letters to project an inflated sense of competency. Be especially wary of anyone who creates a certification and then uses their own letters at their end of their name. Self-certification is sketchy at best.

Action item 1: Don’t be dazzled by a string of letters. Remain neutral and curious.

Action item 2: If someone is self-certifying, proceed with caution.

Professional memberships

The last type of title you might see at the end of someone’s name isn’t actually letters at all, but a series of numbers preceded by a pound sign. All that means is that they are sharing their membership number from a professional organization. Professional memberships require nothing more than paying a fee. That’s it. Not only do these numbers indicate literally nothing about an individual’s qualifications, this practice is almost always a ploy to project an inflated sense of competency. To the untrained eye, the more letters and numbers you have at the end of your name, the more impressive you are!

Action item: If someone is using their membership number as a title, proceed with extreme caution.

#2. Do they cite their sources?

As this profession grows and evolves, we are collectively developing more of an awareness of the behavior sciences and how they impact what we do. That is a good thing! And we are moving in the right direction! However, this budding interest in science means that we are still far from achieving scientific literacy, as a whole. As a result, it has become quite popular across methodologies to throw around scientific terminology and make confident assertions about what science says. This can be as alluring as it is confusing. If one trainer is using fancy words and confidently claiming that science says one thing, and another trainer is using equally fancy words and confidently claiming that science says something mutually exclusive, who do we believe? Is it all just a matter of opinion or perception? Or schools of thought?

We could devote our lives to investigating these questions, but fortunately you don’t need to become a professional philosopher to get some practical, nuts-and-bolts answers that can provide you with some guidance.

A good place to start is by simply asking the behavior professional to back their claims by citing their sources. That’s at least a first step towards gauging the reliability of the professional you’re considering hiring.

Action item: If a behavior professional is providing information that they claim is based in science, ask them to show you the literature supporting their claims. If they can’t or won’t, proceed with caution.

#3. Are their sources sound?

So let’s say you get those citations from the behavior professional you’ve been talking to. Now what?

Again, this is a deep well that we could dive into if we wanted to. There’s a reason that epistemology and related critical thinking skills are taught over multiple courses; there’s a whole lot of ground to cover! But again, you don’t have to become an expert to learn some basic red flags to look out for.

Scenario 1

If their claim is based in science but their source is a webpage, an opinion piece, a YouTube video, a popular book (that itself lacks rigorous citation) or really anything other than primary literature, that right there is a huge red flag. A scientific claim should have a scientific source.

Action item: Investigate what the citation actually leads to.

Scenario 2

If their citations are actual research papers, that’s great! And also, it’s worthwhile to see if those papers were published by a predatory journal. Publication in a predatory journal doesn’t immediately invalidate the paper, it just means that there was no peer review process, so the paper is more likely to have serious methodological flaws that wouldn’t pass the rigor of the peer review process.

To be clear, the peer review process is in itself flawed, and even highly regarded peer-reviewed papers can have methodological flaws. The scientific process is imperfect because it’s being performed by humans, and humans are imperfect. But the beauty of working within the scientific framework is that it is a transparent, accountable, and self-correcting process. Our goal isn’t to get a 100% guarantee; it is to reduce risk.

Action item: Investigate whether the citation was published in a reputable journal.

Scenario 3

If a professional is not making a claim based in science, we can still ask the question, “How do we know that this claim is true?” For example, if a trainer is claiming that they have 100% success with their clients, it wouldn’t make sense to ask them to cite a research paper proving that their claim is true. But we could ask them, “How are you making that assessment?”

If they say something like, “We follow up with our clients 1 month, 6 months, 1 year, and 5 years after they graduate from our program to see if the skills they have learned from us continue to serve them well and their pets continue to pass the welfare and quality of life metrics we have provided for them, and every single client has remained successful up to 5 years after graduation,” ok! That’s a pretty solid assessment on which to base the claim that they have 100% success! Let’s set aside the fact that a 100% success rate is highly improbable; if they were to have kept that level of documentation, it is more likely that their claim is accurate. Anything short of that, however, may indicate that the trainer either doesn’t know enough to really know how to make such assessments or is intentionally misleading people in their marketing.

Action item: Ask them, “How are you making that assessment?” in response to personal claims.

#4. Do they use precise language?

We at Pet Harmony have a mantra that we use to remind ourselves and our colleagues to exercise some intellectual humility:

Undereducation overstates.

What we mean is that, the less we know about a topic, the more likely we are to make overstatements, broad generalizations, and confident assertions. We’re more likely to speak in absolutes like “always”, “never”, or give confident predictions about future events.

Conversely, the more we learn about a topic, the more cautious and precise we become in our language, our predictions, and our assertions.

If someone is using grandiose language in their messaging, be wary. These are just a few examples of the kind of overstatements that you might encounter:

- Claims to be the world’s best dog trainer

- Claims to be revolutionizing the industry, or that they’re introducing something completely new and never before seen

- Claims to have 100% success rate or offers a 100% guarantee

- Claims to be fluent in multiple scientific disciplines despite a lack of any degrees in any of those disciplines

- Claims that science has proven that their system works or is correct or is the best

- Really, claims that science has “proven” anything

This one can be a little bit tricky, because SEO and marketing consultants often teach business owners to use grandiose language, and it can be admittedly difficult to find a balance between writing website copy that is accurate while still writing copy that is good for SEO. There are gray areas on our own website that made us all squeamish and ended up being a compromise between what was suggested and what we ideally would have preferred to say! But when in doubt, ask the behavior professional what they meant by those statements. If they stand behind the hyperbole and insist that yes, they really are the world’s best dog trainer, or yes, their system really is changing the whole industry, or yes, they really can predict your pet’s future behavior with perfect accuracy, that’s a red flag.

Action item: Identify hyperbole and ask for clarification.

#5. Are they receptive to questions and constructive feedback?

From my personal perspective, this last one is arguably the most important one. We’re all human. We all make mistakes. We don’t know what we don’t know. We’re doing the best we can with the information and resources we have available to us at the time. I have made more mistakes, more overstatements, and been wrong more times than I can count. Many of those times have been very public. It happens to all of us. And! When I learn better, I correct my errors and change my behavior.

So someone could fail all of the criteria above, but if you asked them about it, gave them constructive feedback, and offered them resources to learn and do better, and they were willing to learn and grow and change their behavior and do better, they could still end up being a great partner in helping you to achieve your goals. Demonstrating a willingness to exchange knowledge rather than insisting on being right and maintaining some kind of unidirectional power dynamic goes a long, long way in how effective they can be at helping you.

Action item: If you have any concerns about any red flags, talk to them about it! Observe how they respond.

In summary…

At the end of the day, remember that these are just guidelines to help you mitigate risk and increase the chances of choosing a behavior professional who will be effective at helping you to reach your goals in a way that meets both your and your pet’s needs. There are no guarantees. There could, hypothetically, be someone who fails all of the above criteria but still ends up being great for you. Conversely, just because someone passes all of the above criteria with flying colors doesn’t necessarily mean that they’re going to be a good fit for you. These are techniques to help you gauge how reliable someone’s information is–no more, no less. It may still take you a few tries to find the right behavior professional for you, just like it sometimes takes a few tries to find the right doctor or the right therapist or the right personal trainer. Keep at it! You and your pet deserve to enjoy success and find harmony within your home.

Now what?

- Interested in learning more about epistemology? This video is a great place to start.

- When looking for a behavior professional, use the action items provided above to aid in your decision-making process.

- Want to work with someone on the Pet Harmony team? We’d love to work with you! You can schedule your initial appointment here.

Happy training,

Emily